Introduction

I have taken on this project in an attempt to understand the place of women in Pakistani society and to explore the social dynamics that shape it. According to the World Economic Forum's Global Gender Gap Report 2025, Pakistan ranks the lowest in terms of gender parity. This doesn’t surprise me, not as someone living and breathing the patriarchal air in which I was born. But it may surprise others, so I set out to analyze a fraction of published articles on killings in the name of honour.

I chose this topic because I needed to scream. Because women in Pakistan are not just threatened by strangers; we are endangered by fathers, brothers, husbands, those meant to protect us. As bell hooks writes in "Understanding Patriarchy," patriarchy doesn’t benefit anyone. Honour killings are an extreme manifestation of that cruelty, acts that grant men power without accountability, and women death for disobedience. The man proves his so-called honour; the woman pays the price. And while patriarchy harms everyone, it rarely punishes those who enforce it. It rewards their violence with silence.

To understand how this violence is linguistically framed, I conducted a feminist discourse analysis. I relied on Fairclough’s language model, which looks at both text and the broader social practices that shape and are shaped by it. I also drew on feminist theories to ground and expand my interpretations.

Methodology

I analyzed 50 articles published between 2016 and 2025 in major English-language newspapers in Pakistan. I chose this timeline deliberately: in 2016, the Criminal Law (Amendment) (Offences in the Name or Pretext of Honour) Act was passed following the murder of Qandeel Baloch by her brother. Despite this legal intervention, honour killings persist, almost as if the law never came.

Using Excel, I annotated articles by age of victim, relationship to perpetrator, motive, method of killing, and more. I then used Python’s spaCy library for tokenization, lemmatization, and part-of-speech tagging. What emerged was both shocking and heartbreakingly familiar. Victims ranged in age from 13 to 60, mostly women, most often killed by their brothers.

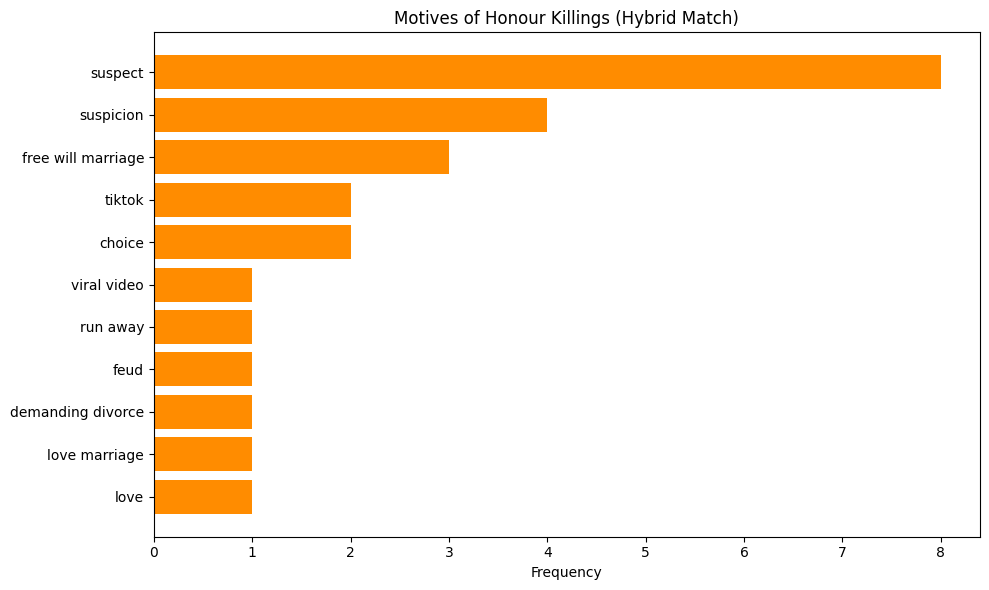

The most frequent motive? “Suspicion”. Articles cited alleged relationships or dishonourable conduct, but these accusations were rarely supported by evidence. As one article put it: "The girl’s family suspected she had established relations with someone.” This is not justice. This is prejudice codified into death.

A word frequency analysis revealed the dominance of words like family, brother, kill, and honour. I turned this into a word cloud, a visual representation of what we fear to say aloud: that family is often the origin of violence, not its antidote.

I also used AntConc to study concordance lines and word clusters. Repeated phrases like "honour killing", "family honour", "killed for honour" framed the crime as cultural duty rather than criminality. They offered a soft veil over brutal acts.

Textual Analysis

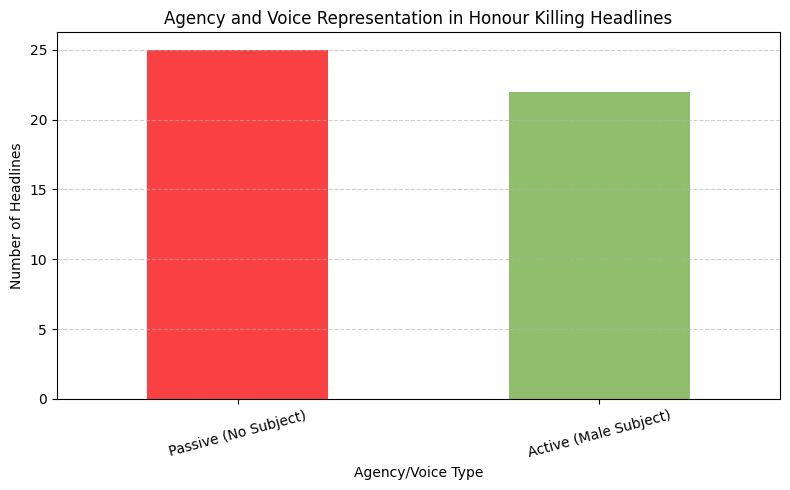

Verbs of violence, killed, murdered, strangled, stoned are overwhelmingly used in the third person and in passive constructions, removing the perpetrator from the frame. Consider: “Woman stoned to death outside Lahore High Court.” The crime is grammatically complete without a killer.

When men do appear as subjects, their agency is clear: “Man kills sister for honour.” Women, meanwhile, are grammatical objects, daughters, wives, mother of seven, rarely named, never individual.

This aligns with Sara Mills’ concept of agency erasure, where grammar itself becomes a weapon, removing women's subjectivity and making their deaths feel like natural consequences.

Headlines rarely acknowledge when the victim is a child. Girls as young as 13 are labeled "women," while male perpetrators are occasionally softened with age-specific terms like "teen." This disparity contributes to a cultural blind spot around child marriage and gender-based violence.

Most cases are triggered by free-will marriages, yet articles opt for euphemisms like "runaway", "marriage for love", or "defying family tradition". This strips women of their right to choose and binds them to patriarchal definitions of propriety.

Drawing on Simone de Beauvoir’s notion of the subject-object relationship, we see that women are always the "other", judged, defined, and punished by male-centric norms. De Beauvoir wrote that women are taught from early on to view themselves through the eyes of others. Honour killings are the fatal consequence of that indoctrination.

Concordance, Clusters, and the Politics of "Honour"

Using AntConc, I explored the lexical company that honour keeps. While the corpus wasn’t large enough for full collocation analysis, even the cluster and concordance lines revealed a clear ideological script:

“Family honour”

"Tradition and honour”

"Murdered for honour"

These aren't just phrases. They are discursive tools that make murder sound respectable and masculinity feel justified. They transform women from humans into symbols, symbols that can be eliminated to restore male pride.

Social Practice: When Language Mirrors Power

These linguistic patterns are deeply intertwined with the structures of patriarchal control. Gayatri Spivak’s question “Can the subaltern speak?” finds a bitter answer here. Women do not get to narrate their choices; they are narrated, erased, and eventually buried.

Deniz Kandiyoti’s idea of the patriarchal bargain also helps explain the complicity of women in these stories. Some murders were facilitated by mothers-in-law or other female relatives, who had internalized a system in which survival means submission, and sometimes sacrifice.

Postcolonial feminists like Chandra Mohanty remind us to resist universalizing the female experience. Honour killings in Pakistan are not simply about male violence, they’re about the intersections of class, tribal codes, economic dependency, and legal inertia.

As Naila Kabeer points out, when women lack legal visibility and economic power, their lives become negotiable. The language of news reports, “dies in suspected honour killing”, upholds this erasure. It is what Spivak calls epistemic violence: the violence of not knowing, not seeing, not naming.

Conclusion: When Grammar Becomes a Grave

This project was meant to be a linguistic analysis, but it turned into a mourning process. Every passive verb, every missing subject, every euphemism felt like another act of complicity.

When media use phrases like “found dead” or “honour killing” without naming the killer, they are not being neutral. They are choosing sides. And that choice has consequences.

Women in Pakistan are not dying because of dishonour. They are dying because society has agreed not to see them as subjects, only as objects in someone else’s story.

To change that, we need to rewrite the story, grammatically, politically, and culturally.

References

Beauvoir, S. de. (1949). The Second Sex.

Butler, J. (1990). Gender Trouble.

Fairclough, N. (1995). Critical Discourse Analysis.

hooks, b. (2004). Understanding Patriarchy.

Kabeer, N. (2005). Gender equality and women's empowerment: A critical analysis of the third millennium development goal. Gender & Development, 13(1), 13–24.

Mills, S. (1995). Feminist Stylistics.

Mohanty, C. T. (1984). Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses.

Spivak, G. C. (1988). Can the Subaltern Speak? In C. Nelson & L. Grossberg (Eds.), Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture (pp. 271–313). University of Illinois Press.

World Economic Forum. (2025). Global Gender Gap Report 2025. https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2025

Government of Pakistan. (2016). Criminal Law (Amendment) (Offences in the Name or Pretext of Honour) Act.

Available at: https://www.dawn.com/news/1288569

📂 GitHub: [View annotated data and scripts]

📖 Medium Summary: [Read the short version]